In light of MTN and Maroc Telecoms’ (unsurprising) revelations that they are looking for acquisition targets on the continent, I thought it worth looking at their potential targets. First up, the classical entry point into markets – incumbents.

The privatisation of incumbents and the liberalisation of telecoms markets is one of the greatest achievements of the European Union and has reaped great dividends in the strength of European telecoms companies on a global scale and in the availability of high quality services to citizens. It’s a model that all other countries should look to and seek to replicate.

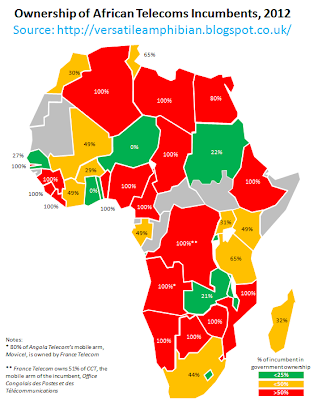

Africa is probably the polar opposite of this situation. As the figure shows, African governments have been almost criminally inept at privatising their state owned telecoms companies. In some cases, this has been simple greed – the example of NetOne in Zimbabwe being a prime example – in others, corruption and incompetence have led to numerous failed processes. Nitel, which now looks headed for ignominious bankruptcy, is by far the best example of the latter. The term basket case was invented for it.

Others have succeeded. Although the Ghanaian government seemingly regrets the price at which it sold Telecom Ghana to Vodafone, I suspect that history will prove the sale to be a smart move. Few African governments have the capital or lines of credit to upgrade the shonky old infrastructure left over from times past, but all of them need the fundamental backbone network services that only a fixed line incumbent can realistically provide. This need is particularly acute in those countries enjoying rapid economic growth, necessitating high quality (especially B2B) Internet services that mobile hasn’t a prayer of supplying.

The large regional and global telecoms players certainly do have capital and, given the reins, the ability to make it count operationally. In my view, selling early - even relatively cheaply - will unlock massive economic benefits in service sector growth, public sector efficiency, education and overall competitiveness. Keeping hold of telecoms incumbents in the hope that they will one day become highly valued assets is folly. What’s more likely is that if they’re retained alternative networks will come in and make them even less viable. Or worthless, as is probably now the case with Nitel.

Flipping the story around, investors should be interested in fixed incumbents provided they are able to negotiate large guarantees from governments over the status of telecom and ICT deals. As African governments modernise, their need to ICT services will sky rocket and telecoms groups will be able to make super-profits by exploiting assets they build for the public sector for commercial customers in the markets. In my view, the business model for incumbent acquirers should be grounded on long term B2B revenues.

That’s probably enough on incumbents. Each case is quite different so I’d rather not over-generalise! It’ll be fascinating to see what transpires in the months and years ahead.

The privatisation of incumbents and the liberalisation of telecoms markets is one of the greatest achievements of the European Union and has reaped great dividends in the strength of European telecoms companies on a global scale and in the availability of high quality services to citizens. It’s a model that all other countries should look to and seek to replicate.

Africa is probably the polar opposite of this situation. As the figure shows, African governments have been almost criminally inept at privatising their state owned telecoms companies. In some cases, this has been simple greed – the example of NetOne in Zimbabwe being a prime example – in others, corruption and incompetence have led to numerous failed processes. Nitel, which now looks headed for ignominious bankruptcy, is by far the best example of the latter. The term basket case was invented for it.

The large regional and global telecoms players certainly do have capital and, given the reins, the ability to make it count operationally. In my view, selling early - even relatively cheaply - will unlock massive economic benefits in service sector growth, public sector efficiency, education and overall competitiveness. Keeping hold of telecoms incumbents in the hope that they will one day become highly valued assets is folly. What’s more likely is that if they’re retained alternative networks will come in and make them even less viable. Or worthless, as is probably now the case with Nitel.

Flipping the story around, investors should be interested in fixed incumbents provided they are able to negotiate large guarantees from governments over the status of telecom and ICT deals. As African governments modernise, their need to ICT services will sky rocket and telecoms groups will be able to make super-profits by exploiting assets they build for the public sector for commercial customers in the markets. In my view, the business model for incumbent acquirers should be grounded on long term B2B revenues.

That’s probably enough on incumbents. Each case is quite different so I’d rather not over-generalise! It’ll be fascinating to see what transpires in the months and years ahead.

Comments

Post a Comment